The Aftermath

The Tiananmen Square self-immolation was a turning point in the state’s campaign against Falun Gong. Public sympathy for the group declined markedly, both in China and abroad. Reports of torture and Falun Gong deaths in custody soared…

China’s state-run press generally stifled news of political protests, but on this occasion the official news outlets reported on the event with unusual enthusiasm. Within two hours, authorities release details to the foreign press:

Hoodwinked by the evil fallacies …of the Falun Gong cult, five Falun Gong followers set themselves ablaze on Tiananmen Square.

—Xinhua News Agency, January 23 2001

Subsequent editorials in the country’s leading newspapers piled on: “The tragedy once again demonstrated the evil nature of Falun Gong,” (Xinhua News Agency, January 30, 2001) which “tortures human life, endangers the whole society and infringes on human rights.” (Xinhua News Agency, February 2, 2001) Speaking only to approved state-run media outlets, the surviving protesters said they had been duped by Falun Gong’s teachings, believing they could reach nirvana through fiery self-sacrifice. They expressed immediate regret for their actions, and thanked the police and government for saving them.

Chinese authorities used the incident as justification for the mass detentions and “re-education” of Falun Gong devotees, declaring that the self-immolation was proof that Falun Gong “must be rooted out for the sake of long-term social stability and safety of the people.”

The government said [the self-immolation] proved the group was evil…since then Beijing has ratcheted up the [anti-Falun Gong] campaign to a fever pitch, bombarding citizens with an old, communist-style propaganda war replete with meetings, denunciations and blanket coverage in the government-run media.”

—Ian Johnson, Wall Street Journal

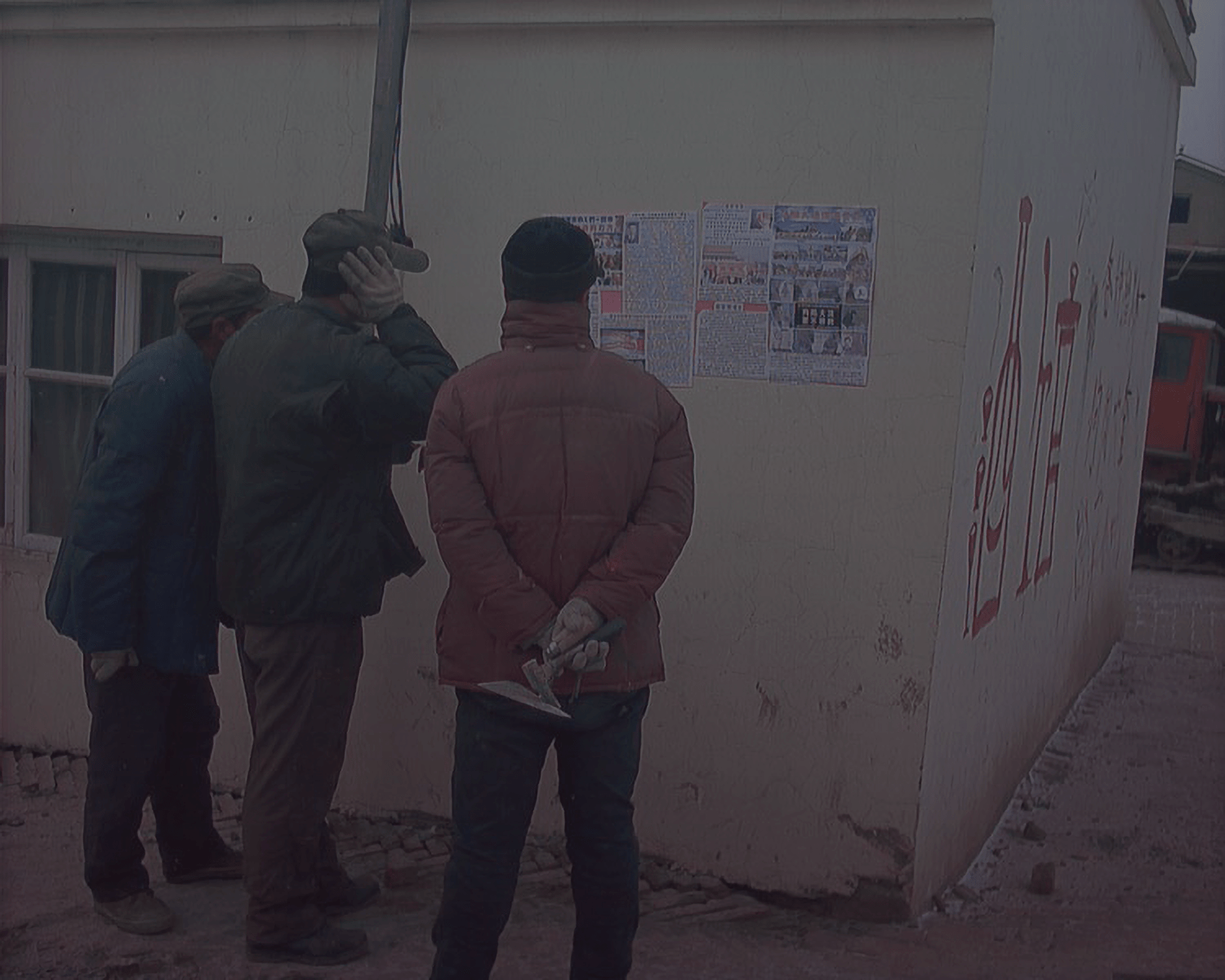

For months on end, the official press was filled with invectives against Falun Gong. Television channels broadcast images of a charred 12-year-old girl writhing on the ground, calling for the mother who died in the flames. In a throwback to Maoist campaigns of earlier decades, students across China were made to sign mass petitions denouncing the group, and memorized anti-Falun Gong poems whose words were shown dripping in blood. Work units were mobilized to assist in the struggle, and cadres and government officials were forced into indoctrination sessions to ensure they toed the party’s line. The propaganda barrages—and the horrifying images of burning bodies—were ubiquitous and inescapable.

The there is a sense here that, after a year and a half of flailing, the government finally scored a propaganda coup last week against the outlawed spiritual group.

—Erik Eckholm, New York Times, February 4 2001

Public sympathy for the Falun Gong evaporated in the wake of the incident, and Chinese citizens began associating Falun Gong with feelings of disgust and revulsion. The shift in public opinion was palpable, and people who had previously sympathized with the group were converted to the government’s side.

People were quite sympathetic to Falun Gong members because they were peaceful and friendly and wouldn't disturb anybody," said one Beijing hotel worker to the LA Times. "But now it seems like they've become people's enemies, which makes us hate them…These people are really crazy.

—Henry Chu, Los Angeles Times, February 9, 2001

Outside China, too, the public image of Falun Gong suffered a blow. Until that time, it had largely been perceived as a group of peaceful meditators confronting an oppressive regime, but practitioners were now increasingly seen as religious fanatics undermining China’s march toward modernity. By the year’s end, Western news outlet all but completely stopped reporting on human rights abuses against Falun Gong practitioners in China.

Soon after news broke of the self-immolation, Falun Gong sources overseas began questioning the government’s official narrative. Notably, they pointed out that Falun Gong’s teachings strictly forbid killing and suicide, and that their teachings do not include references to “nirvana,” as claimed by the Chinese press. The notion that a person could set herself on fire to reach heaven simply had no basis in Falun Gong beliefs.

Falun Gong leaders insist that the [self-immolators] could not have been members of their movement, which promotes a mix of Buddhism, Taoism and traditional Chinese breathing exercises. They have said Falun Gong clearly forbids both violence and suicide and have suggested the government may have staged the incident.

—Philip P. Pan, The Washington Post, February 4 2001

In the days and weeks that followed, Falun Gong practitioners identified other discrepancies in the government’s account: they noted that police had camera crews and firefighting equipment on hand at the time of the self-immolation, and that a press release was issued immediately by the state-run news agency, bypassing usual approval and vetting processes. They highlighted findings by the Washington Post that one of the self-immolators was a prostitute with no known affiliation with Falun Gong. Finally, they pointed to the CCTV footage itself, which appeared to show police striking one of the victims forcefully on the head, and to scenes from the hospital, which raised questions about whether some aspects of the CCTV story were staged for emotional effect.

Among most Falun Gong practitioners—as well as a number of sceptical journalists and international observers—an alternative theory of the self-immolation emerged. They contended that the victims were not Falun Gong practitioners at all, but rather that the entire event was planned by the government as a propaganda piece.

Freed from the constraints of public censure or international scrutiny, Beijing began sanctioning the “systematic use of violence” against Falun Gong adherents who refused to recant their faith. Directives from Beijing ordered that practitioners be rooted out neighbourhood by neighbourhood; no one was to be spared. The Wall Street Journal described a “sharply intensified campaign of repression and control”, characterized by mass extrajudicial imprisonment, propaganda, and torture. Deaths in custody became increasingly common.

The crackdown has benefited from a turn in public opinion against Falun Gong since five purported members set themselves on fire in Tiananmen Square… As Chinese society turned against Falun Gong, pressure on practitioners to abandon their beliefs increased, and it became easier for the government to use violence against those who did not

—Philip Pan, The Washington Post, August 5 2001

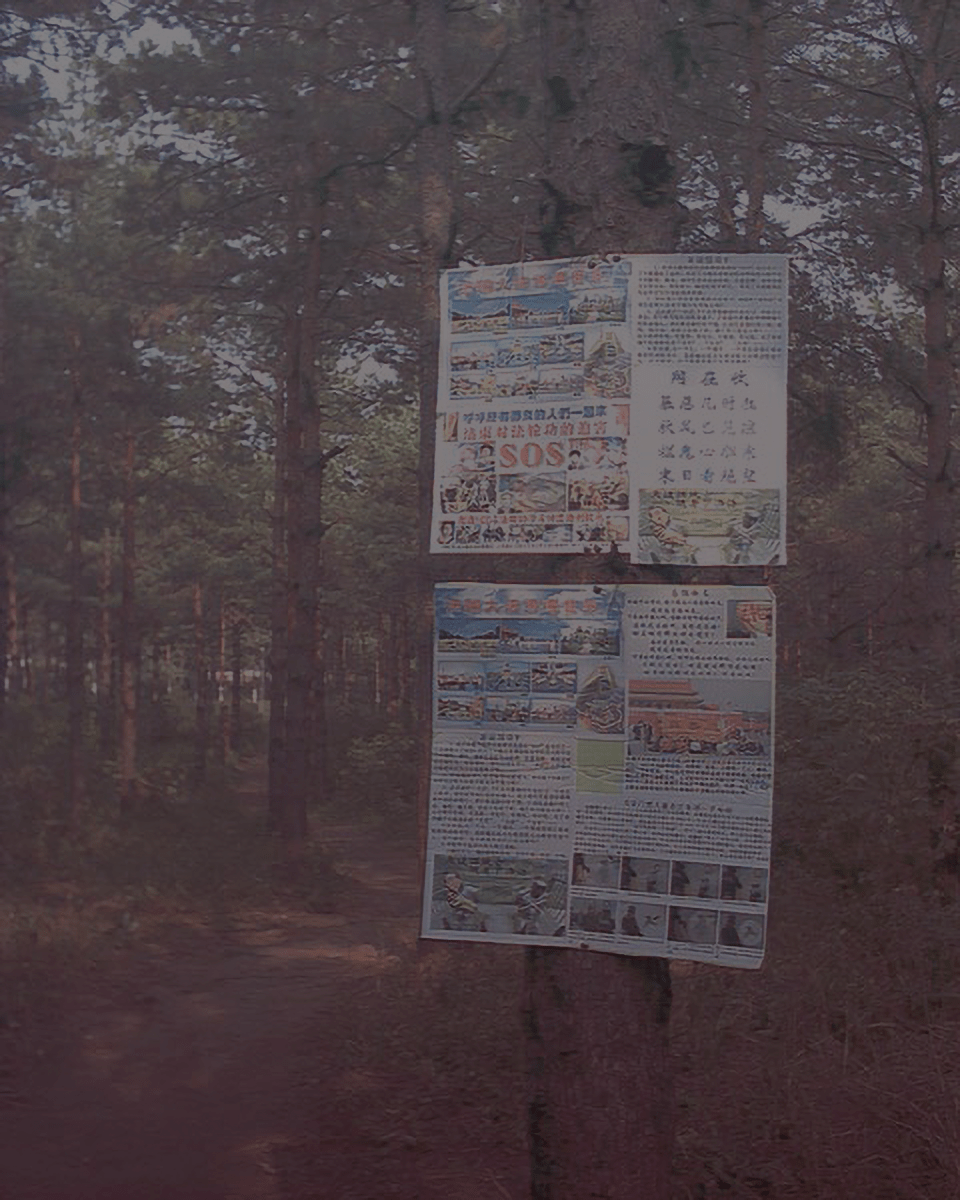

The Tiananmen self-immolations served another important objective: it spelled the end of persistent, peaceful Falun Gong protests on Tiananmen Square, which had become a significant irritant to the leaders in Beijing. Instead, many Falun Gong practitioners began resorting to more low-key forms of resistance, publishing literature or distributing DVDs documenting the persecution and challenging the Party’s narratives.

Under guidance from a new office in Beijing, each province has set up a team to coordinate the anti-Falun Gong battle using a two-pronged strategy: prison or ''re-education'' for leaders and recalcitrant members; intense propaganda demonizing the group for everyone else.

—Erik Eckholm and Elisabeth Rosenthal, New York Times, March 9 2001

In the absence of sustained international attention or high-profile public protests, the Falun Gong story faded from view. Although there is evidence that suggests a contradicting story, no further investigations of the Tiananmen Square self-immolation were ever conducted by China-based journalists.