The Suppression

In July 1999, the Chinese Communist Party launched a nationwide crackdown to eliminate Falun Gong, a peaceful spiritual practice with tens of millions of followers. An intense campaign of state propaganda, mass detentions, and torture followed…

Falun Gong, sometimes called Falun Dafa, was once a popular spiritual discipline in China.

The practice combined meditation and slow-moving qigong exercises with a set of moral teachings based in Buddhist cultivation tradition. At the heart of its philosophy are the tenets of “Truthfulness, Compassion, and Forbearance,” which are said to represent the ultimate expression of the Buddhist Dharma or the Dao.

Although the practice lacked the formalities of an institutional religion—having no churches or temples, systems of membership, tithing or fees—it nonetheless reflected a view that humankind is connected to higher realms, and that through diligent personal practice, a person might achieve better health and, ultimately, enlightenment.

Falun Gong was introduced publicly in 1992 by a Master Li Hongzhi. After decades of life under Communism, it represented a return to traditional values, and responded to a yearning for deeper meaning and purpose in an increasingly materialistic society.

By 1999, Falun Gong was estimated to have upwards of 70 million practitioners.

In the early and mid-1990s, several branches of the Chinese government actively encouraged Falun Gong’s growth, viewing it as a means of improving public health and morality.

But by the late 1990s, Falun Gong was estimated to have up to 70 million adherents, rivaling the size of the Chinese Communist Party itself. Its philosophy, moreover, bore distinctly religious overtones that put it in opposition to the prevailing atheistic and materialist orthodoxy. And although the practice had no political aspirations, it had resisted co-optation and control by the state. In a country that brooks no tolerance for independent civil society groups, this proved a dangerous line to walk.

Disagreements began appearing within the Chinese Communist Party, with some leaders arguing that Falun Gong needed to be suppressed. State-run publishing houses were banned from printing Falun Gong books, and public meditation sites were increasingly subject to police interference.

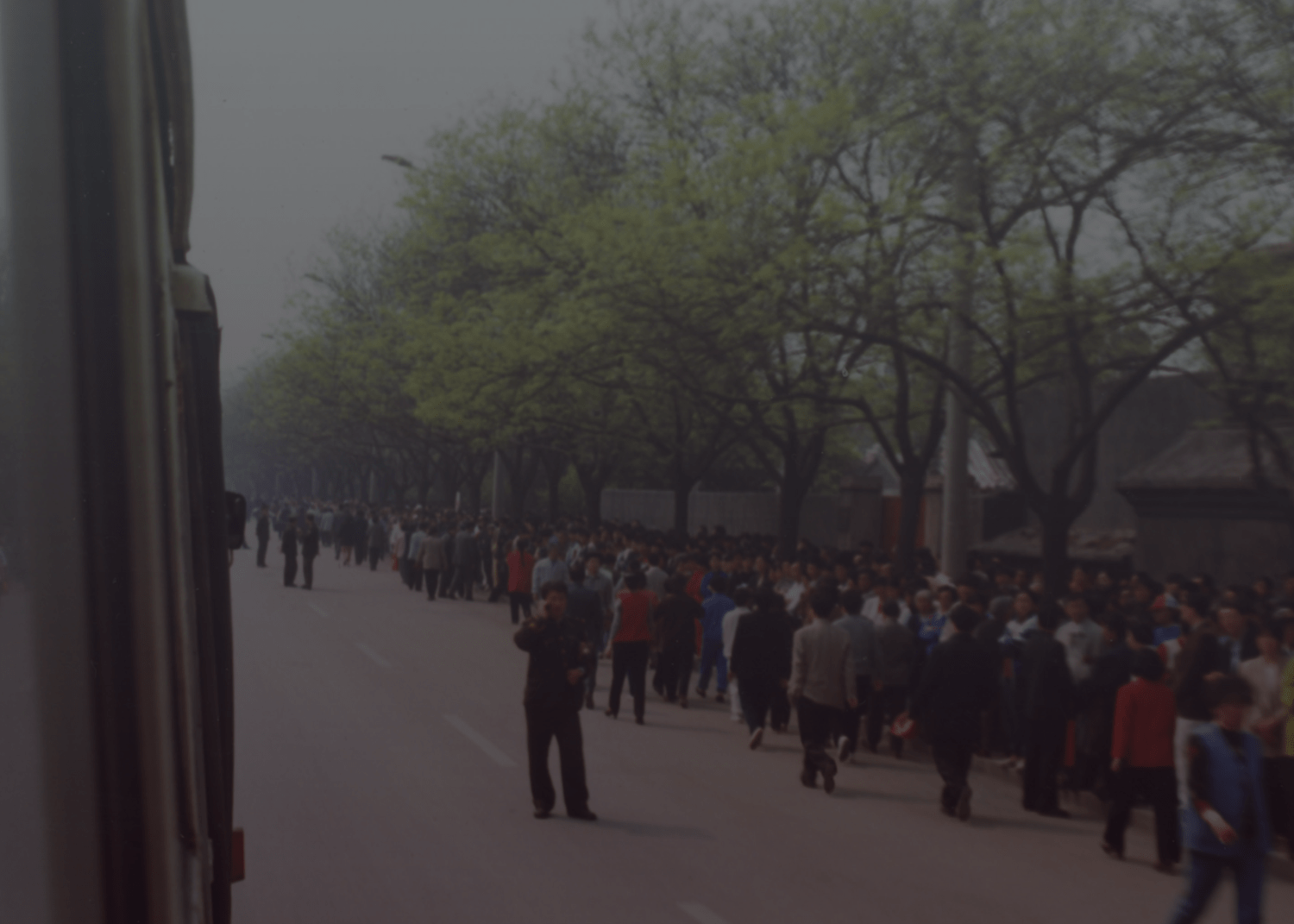

Tensions culminated on April 25, 1999, when 20,000 Falun Gong adherents gathered quietly outside the central government compound at Zhongnanhai to request an end to escalating harassment against them.

That evening, Communist Party leader Jiang Zemin ordered that Falun Gong must be crushed.

In the early morning hours of July 20, 1999, thousands of Falun Gong adherents across the country were taken from their homes by security agents and held in detention. Two days later, on July 22, the official announcement came that practicing Falun Gong was now forbidden.

The Party decided to crush Falun Gong because it cannot tolerate an organization separate from its control... The crackdown against Falun Gong is by far China's biggest since soldiers crushed student-led democracy demonstrations at Tiananmen Square in Beijing in June 1989. The government has branded Falun Gong “dangerous” and “evil” and has mobilized thousands of security personnel and the state-run press to smash the group. —John Pomfret, The Washington Post, Nov. 12 1999

A massive suppression followed: police, courts, schools, neighborhoods, and work units were mobilized to “struggle” against Falun Gong. State-run media went into overdrive to denounce the group as a threat to social stability and the Communist system. Millions of Falun Gong books were burned or destroyed, and dissenting views were silenced. Lawyers were forbidden from representing Falun Gong clients, who were sent by the tens of thousands to prisons and labor camps.

Local officials were told to use “any means necessary” to force Falun Gong adherents to renounce their beliefs. By the end of the year, reports of torture and deaths in police custody were growing increasingly common.

The suppression campaign was coordinated by the “610 Office”—an extrajudicial security organ created with the express purpose of eliminating Falun Gong.

After the suppression campaign began, many Falun Gong adherents went underground or stopped practicing entirely, fearing reprisals. Yet the group showed unexpected resilience, as many practitioners not only continued practicing, but openly demonstrated against the ban.

Beginning in the fall of 1999, dozens or hundreds of Falun Gong practitioners daily went to Tiananmen Square to appeal to the government. Some held banners or quietly meditated, while others distributed leaflets making their case. Police responded by arresting the demonstrators, dragging or forcing them into waiting vans to be sent into detention.

Confronted with the full weight of China's security apparatus, Falun Gong should have died a quick death. But unlike the dissidents who occasionally challenge the Communist Party, Falun Gong activists haven't been stopped, despite mass arrests, beatings and even killings. Instead, a hard core continues to protest, with several dozen arrested every day in downtown Beijing when they try to unfurl banners calling for their group's legalization. A year on, Falun Gong faithful have mustered what is arguably the most sustained challenge to authority in 50 years of Communist rule. —Ian Johnson, The Wall Street Journal, April 20, 2000

The daily protests on Tiananmen Square garnered international media attention, and China came under increasing scrutiny for its often brutal handling of non-violent Falun Gong adherents.